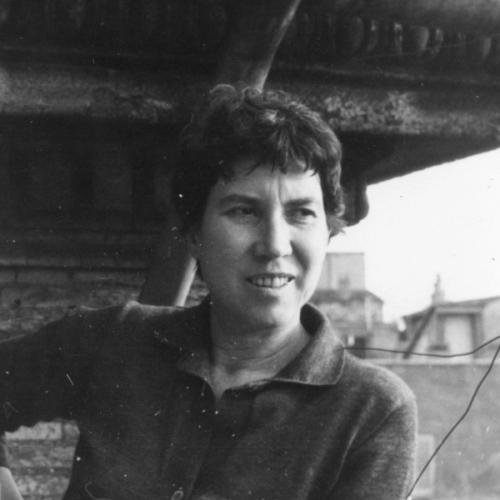

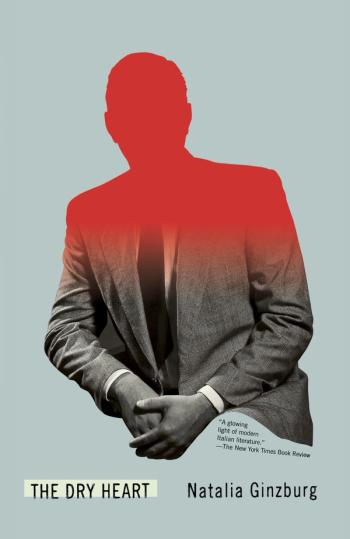

Natalia Ginzburg

Natalia Ginzburg (1916–1991), “who authored twelve books and two plays; who, because of anti-Semitic laws, sometimes couldn’t publish under her own name; who raised five children and lost her husband to Fascist torture; who was elected to the Italian parliament as an independent in her late sixties—this woman does not take her present conditions as a given. She asks us to fight back against them, to be brave and resolute. She instructs us to ask for better, for ourselves and for our children” (Belle Boggs, The New Yorker).

“Ginzburg is a unique voice and there’s a direct simplicity to her prose that makes her dry observations all the more riveting” (Hephzibah Anderson, The Guardian)