As author

As translator

As contributor

Lydia Davis

Lydia Davis, a MacArthur Fellow, is the author of The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis and the translator of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary.

Lydia Davis, a MacArthur Fellow, is the author of The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis and the translator of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary.

New Directions is happy to announce the publication of a new series of Poetry Pamphlets, a reincarnated version of the “Poet of the Month” and “Poets of the Year” series James Laughlin published in the 1940s, which brought out such eclectic hits as William Carlos Williams’s The Broken Span, Delmore Schwartz’s poetic play Shenandoah, John Donne’s Some Poems and a Devotion, and Yvor Winters’s Giant Weapon, among many others. The New Directions Poetry Pamphlets will highlight original work by writers from around the world, as well as forgotten treasures lost in the cracks of literary history.

Included in this set of four are:

Sorting Facts, or Nineteen Ways of Looking at Marker, by Susan Howe

Two American Scenes, by Lydia Davis & Eliot Weinberger

Pneumatic Antiphonal, by Sylvia Legris

The Helens of Troy, New York, by Bernadette Mayer

Two remarkable prose stylists — friends since high school — transform found material from the nineteenth century into mesmerizing poem-essays.

It was given to me, in the nineteenth century, to spend a lifetime on his earth. Along with a few of the sorrows that are appointed unto men, I have had innumerable enjoyments; and the world has been to me, even from childhood, a great museum. — Lydia Davis

Bad rapids. Bradley is knocked over the side; his foot catches under the seat and he is dragged, head under water. Camped on a sand beach, the wind blows a hurricane. Sand piles over us like a snowdrift. — Eliot Weinberger

Translated by Lydia Davis

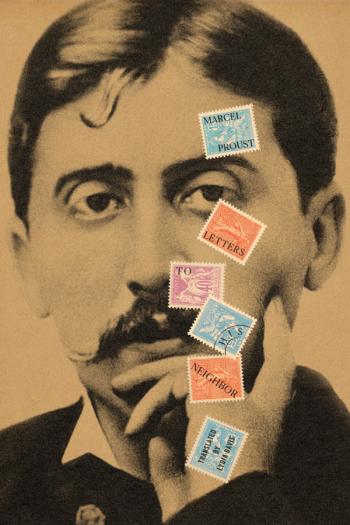

Marcel Proust’s genius for illuminating pain is on spectacular display in this recently discovered trove of his correspondence, Letters to His Neighbor. Already suffering from noise within his cork-lined walls, Proust’s poor soul was not ready for the fresh hell of his new upstairs neighbor, Dr. Williams, a dentist with a thriving practice directly above his head.

Chiefly to Mme Williams, these ever-polite letters (often accompanied by flowers, books, or compliments) are frequently hilarious—Proust couches his pained frustration in gracious eloquence. In Lydia Davis’s hands, the digressive brilliance of his sentences shines: “Don’t speak of annoying neighbors, but of neighbors so charming (an association of words contradictory in principle since Montesquiou claims that most horrible of all are 1) neighbors 2) the smell of post offices) that they leave the constant tantalizing regret that one cannot take advantage of their neighborliness.”

Lydia Davis has written a generous translator’s note, tracing much of what we can know about Proust’s perpetually darkened room; she details the furnishings as well as the life he lived there: burning his powders, talking with friends, hiring musicians, and most of all, suffering. Letters to His Neighbor is richly illustrated with facsimile letters and photographs—catnip for lovers of Proust.

Madame,

I have been wanting for a long time to express to you my regret that the sudden arrival of my brother prevented me from writing to you during the last days of your stay in Paris, then my sadness at your leaving. But you have bequeathed to me so many workers and one Lady Terre—whom I do not dare call, rather, “Terrible” (since, when I get the workers to extend the afternoon a little in order to move things ahead without waking me too much, she commands them violently and perhaps sadistically to start banging at 7 o’clock in the morning above my head, in the room immediately above my bedroom, an order which they are forced to obey), that I have no strength to write and have had to give up going away. How right I was to be discreet when you wanted me to investigate whether the morning noise was coming from a sink. What was that compared to those hammers? “A shiver of water on moss” as Verlaine says of a song “that weeps only to please you.” In truth, I cannot be sure that the latter was whispered in order to please me. As they are redoing a shop next door I had with great difficulty got them not to begin work each day until after two o’clock. But this success has been destroyed since upstairs, much closer, they are beginning at 7 o’clock. I will add in order to be fair that your workers whom I do not have the honor of knowing (any more than the terrible lady) must be charming. Thus your painters (or your painter), unique within their kind and their guild, do not practice the Union of the Arts, do not sing! Generally a painter, a house painter especially, believes he must cultivate at the same time as the art of Giotto that of Reszké. This one is quiet while the electrician bangs. I hope that when you return you will not find yourself surrounded by anything less than the Sistine frescoes… I would so much like your voyage to do you good, I was so sad, so continually sad over your illness. If your charming son, innocent of the noise that is tormenting me, is with you, will you please convey all my best wishes to him and be so kind as to accept Madame my most respectful regards.

Marcel Proust

Translated by Lydia Davis

Gorgeously translated by Lydia Davis, the miniature stories of A. L. Snijders might concern a lost shoe, a visit with a bat, fears of travel, a dream of a man who has lost a glass eye: uniting them is their concision and their vivacity. Lydia Davis in her introduction delves into her fascination with the pleasures and challenges of translating from a language relatively new to her. She also extolls Snijders’s “straightforward approach to storytelling, his modesty and his thoughtfulness.”

Selected from many hundreds in the original Dutch, the stories gathered here—humorous, or bizarre, or comfortingly homely—are something like day-book entries, novels-in-brief, philosophical meditations, or events recreated from life, but—inhabiting the borderland between fiction and reality—might best be described as autobiographical mini-fables.

Translated by Susan Bernofsky, Lydia Davis and Christopher Middleton

An elegant collection, with gorgeous full-color art reproductions, Looking at Pictures presents a little-known aspect of the eccentric Swiss writer’s genius. His essays consider Van Gogh, Manet, Rembrandt, Cranach, Watteau, Fragonard, Bruegel, and his own brother Karl. The pieces also discuss general topics such as the character of the artist and of the dilettante as well as the differences between painters and poets. Each piece is marked by Walser’s unique eye, his delicate sensitivity, and his very particular sensibilities—and all are touched by his magic screwball wit.

Osama Alomar, in his poetic fictions, embodies the wisdom of Kahlil Gibran filtered through the violent gray absurdity of Assad’s police state. Fullblood Arabian is the first English publication of Alomar’s strange, often humorously satirical allegories, where good and evil battle with indifference, avarice, and compassion in striking imagery and effervescent language.

I read in a book the following piece of wisdom: “He who remains silent in the face of injustice is a mute Satan.” I went out into the street and saw Satan everywhere.

Articles: