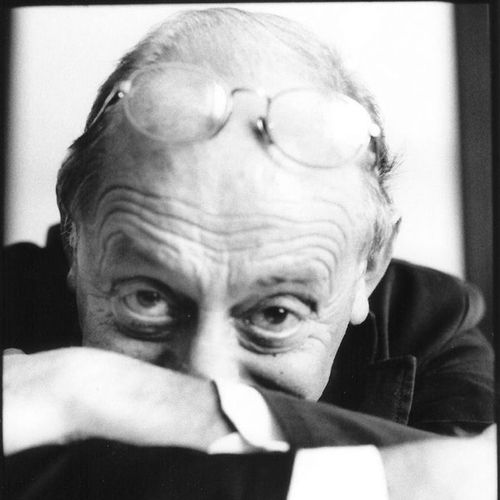

Antonio Tabucchi

Antonio Tabucchi was born in Pisa in 1943 and died in Lisbon, his adopted home, in 2012. The son of a horse trader, he studied literature and philosophy before taking up writing himself. Over the course of his career he won France’s Medicis Prize for Indian Nocturne, the Italian PEN Prize for Requiem, and the Aristeion European Literature for Pereira Declares. A staunch critic of Italian ex-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, he once said that “democracy isn’t a state of perfection, it has to be improved, and that means constant vigilance.”