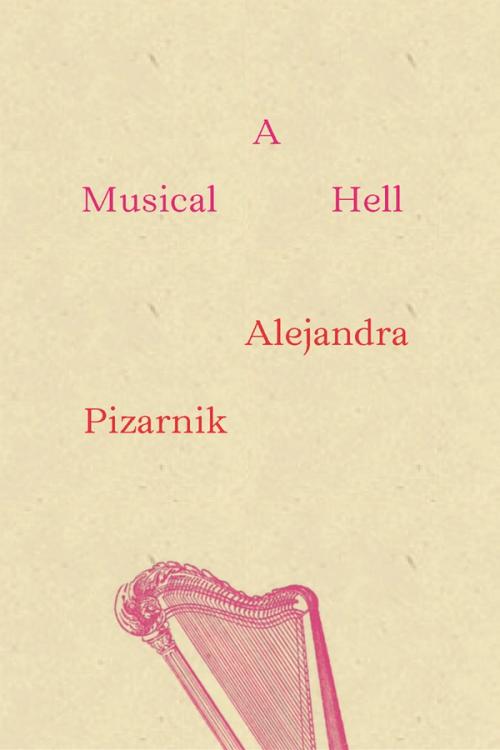

A Musical Hell

by Alejandra Pizarnik

Translated from Spanish by Yvette Siegert

“An aura of legendary prestige surrounds the work of Alejandra Pizarnik,” writes César Aira. Her last collection to be published before her suicide in 1972, A Musical Hell is the first book of poems by Pizarnik to be published in its entirety in the U.S. Pizarnik writes at the edge of poetic impossibility, opening with a blues singer, expanding into silence, and closing into a theater of shadows and songs of the drowned.

— The flower of distance is blooming. I want you to look through the window and tell me what you see: inconclusive gestures, illusory objects, failed shapes.… Go to the window as if you’d been preparing for this your entire life.

Articles:

Review of A Musical Hell in the New York Journal of Books

Paperback(published Jul, 10 2013)

- ISBN

- 9780811220965

- Price US

- 10.95

- Price CN

- 11.99

- Page Count

- 48