Yoko Tawada

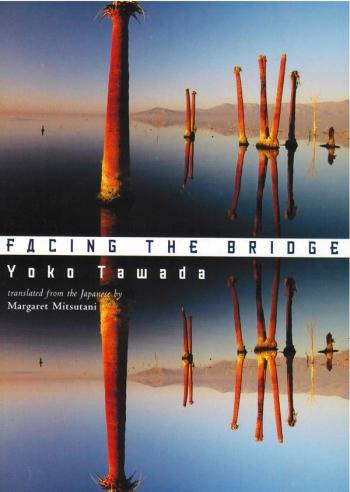

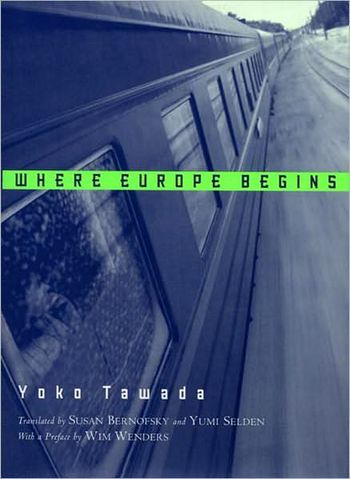

Yoko Tawada was born in Tokyo in 1960, moved to Hamburg when she was twenty-two, and then to Berlin in 2006. She writes in both Japanese and German, and has published several books—stories, novels, poems, plays, essays—in both languages. She has received numerous awards for her writing including the Akutagawa Prize, the Adelbert von Chamisso Prize, the Tanizaki Prize, the Kleist Prize, and the Goethe Medal. New Directions publishes her story collections Where Europe Begins (with a Preface by Wim Wenders) and Facing the Bridge, as well her novels The Naked Eye, The Bridegroom Was a Dog, Memoirs of a Polar Bear, and The Emissary.

Photo credit: Nina Subin