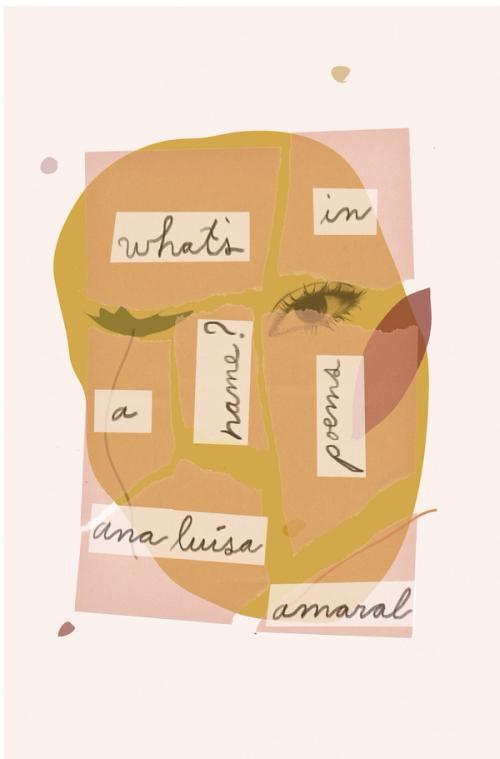

The first installment in our “Voyage Around My Room” series by Portuguese poet Ana Luísa Amaral and translated by Margaret Jull Costa.

My daughter and I gave her the name when we went to fetch her from a shelter called Two Hands for Four Paws. It was, I recall, a bright sunny day with a clear blue sky. And she, a tiny terrified ball of warm fur, wriggled her way inside the sleeve of my jacket and stayed there until we arrived home and took her into the living room, where she immediately went and hid under one of the sofas. Her much-loved and never-forgotten predecessor was called Lily Marlene. “What about calling her Millie?” said my daughter. “All right, Millie Dickinson it is,” I replied. And that’s how she became Millie: encapsulated in a word, a creature as unique as a fingerprint, shaped by language like everything else in this world to which we all belong.

While she has almost the same name as the American poet who once declared “I dwell in Possibility” (with a capital P, just to confuse future readers even more), the two have little else in common. Millie lacks the ethereal, fragile air we see in the daguerreotype of the poet taken in 1848. We are also perfectly aware that Millie isn’t human, although there’s often a most uncanine look of liquid tenderness in her eyes. Lying beside me on the eiderdown, her body snuggled up against mine, she’s a comforting presence, one that exudes pure well-being and contentment. And she responds to me in her own language, which I’ve learned to understand over the years, even more so now that we’re closeted together here. Just like that Amherst recluse who, after the age of thirty, never left the house, and yet who travelled further than anyone, peering into volcanoes, infinite seas, and atoms all the colors of the rainbow.

In these days of reclusion, apart from brief sorties with Millie for hygienic purposes, I travel between my bedroom and the living room, with occasional visits to the verandah on sunny days, and a few hours spent in my study. My study, though, is colder and darker, and so I mostly travel around this large living room full of books, with three sofas, a piano, and photographs of loved ones, both human and animal, some still alive, others no longer with me, like Lily Marlene, who is there next to Margarida, and who are both alive in a way – for wasn’t it that delicate, drunken genius of a Portuguese poet who said “death is the bend in the road, dying is simply ceasing to be seen”?

As I was saying, being stuck indoors like this involves me journeying between bedroom, study and living room. And as I was about to say before I mentioned that great inventor of heteronyms – who was also a recluse in his way, giving each heteronym his own astrological chart, profession, name and family, and his own way of seeing the world – what I was going to say was that Millie Dickinson follows me wherever I go, her paws clattering over the wooden floor like castanets – shades of Lorca. Right now, I’m sitting on the gray sofa (I can also travel between the two other sofas, both of which are red), and if I look to my right, out on the verandah I can see my azalea, which came into glorious flower a week ago. Spring this year will be in much better health, with almost no pollution to lay it low, without the dry cough that usually afflicts the leaves of its trees – but that’s another subject entirely.

If I get up now, Millie will follow me, and because I mentioned Spring, the other Millie probably will too. The Amherst Emily will creep down from that shelf in the corridor, where she’s cosily seated next to Walt, in order to whisper in my ear: “A little Madness in the Spring / is wholesome even for the King, / but God be with the Clown - / who ponders this tremendous scene - / this whole Experiment of Green - / as if it were his own!” And I, touched and weary now from all that travel, will say: Thank you.

—Porto, April 2020

Retrato de pequena viagem interior, com Millie (Dickinson), Fernando Pessoa, um pouco de Lorca, e primavera ao fundo

Demos-lhe o nome quando a fomos buscar, a minha filha e eu, a um abrigo chamado Duas mãos para quatro patas. Lembro-me que estava um dia de sol, céu aberto, luz claríssima. E ela, uma minúscula bola aterrada de pêlo quente, enfiou-se pela manga do meu casaco e lá ficou até chegarmos a casa, e ela entrar connosco na sala, onde se escondeu debaixo de um sofá. Lily Marlène chamara-se a sua antecessora bem-amada e nunca esquecida. “E se a chamássemos Millie?”, perguntou a minha filha. “Millie Dickinson, então”, repliquei eu. E assim ela ficou: escolhida numa palavra, criatura única como impressão digital, a linguagem dizendo o mundo do qual todos fazemos parte.

Embora tenha quase o mesmo nome da poeta americana que um dia disse habitar a Possibilidade (a palavra assim, com maiúsculas, para confundir ainda mais os leitores a haver), não as ligam grandes parecenças. Não tem aquele ar etéreo e frágil que vemos no daguerreótipo da poeta, tirado em 1848. Sabemos cá em casa que ela não é humana, embora o seu olhar seja tantas vezes de uma ternura líquida e muito pouco canina. Mas ao meu lado, na cama, o seu corpo encostado a mim por cima do edredão é um corpo aconchegante que suspira do mais puro bem-estar e felicidade. E responde-me na sua língua que eu aprendi a conhecer cada vez melhor, mais ainda agora, que estamos aqui fechadas. Como a reclusa de Amherst, que, a partir dos trinta anos, deixou de sair de casa. Mas que viajou como ninguém, vendo por dentro vulcões, mares infinitos, átomos irisados de mil cores.

Nestes dias de reclusão, além dos curtíssimos passeios higiénicos necessários à Millie, as minhas viagens são entre o quarto e a sala, com breves passagens pela varanda, se está sol, e umas horas no escritório. Mas o escritório é mais frio, e tem menos luz, de maneira que é sobretudo nesta sala grande que mais viajo, uma sala cheia de livros, com três sofás, um piano, fotografias de seres amados, pessoas e animais, umas vivas, outras, já não comigo, como a Lili Marlène, que ali está ao lado da Margarida, as duas de certa forma vivas – pois não era o poeta português, esse delicado e bêbedo génio de nós todos, que dizia “a morte é a curva da estrada, morrer é só não ser visto”?

Estar assim entre paredes é também viajar entre quarto, escritório e sala, dizia eu. E, se não se tivesse intrometido o grande inventor de heterónimos, cada qual com seu signo, sua profissão, seu nome próprio e de família, sua forma de ver o mundo de dentro, ele também de certa maneira um recluso, aquilo que eu ia há pouco acrescentar era que a Millie Dickinson me segue para onde quer que eu vá, as suas patas martelando o chão de madeira, como castanholas, a apetecer poema de Lorca. Agora mesmo, estou sentada no sofá cinzento (posso também viajar entre os dois outros sofás, ambos vermelhos) e se olho para a direita vejo lá fora a minha azálea que floriu gloriosa uma semana atrás. A primavera este ano será saudável, quase sem poluições a adoecer-lhe o corpo, sem aquela tosse seca de que costumam sofrer as folhas das suas árvores – mas esse seria outro tema de conversa.

Se agora me levantar, a Millie virá atrás de mim; e provavelmente, e porque falei em primavera, também a outra, a Emily, a americana de Amherst, sairá com passinhos leves do fundo daquela prateleira do corredor, onde se aconchega ao lado de Walt, a dizer-me baixinho ao ouvido: “A little Madness in the Spring / is wholesome even for the King, / but God be with the Clown - // who ponders this tremendous scene - / this whole Experiment of Green - / as if it were his own!”. E eu, comovida e cansada de tanto viajar, dir-lhe-ei: obrigada –

Published