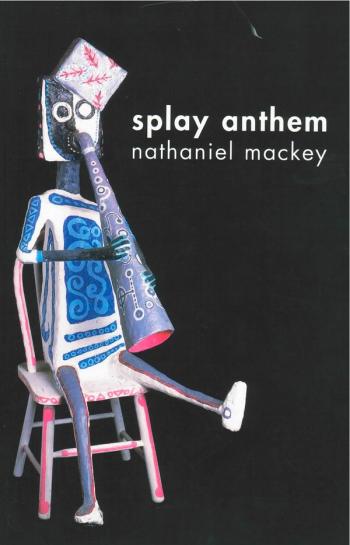

Part antiphonal rant, part rhythmic whisper, Nathaniel Mackey’s new collection of poems, Splay Anthem, takes the reader to uncharted poetic spaces. Divided into three sections—“Braid,” “Fray,” and “Nub” (one referent Mackey notes in his stellar Introduction: “the imperial, flailing republic of Nub the United States has become, the shrunken place the earth has become, planet Nub”)—Splay Anthem weaves together two ongoing serial poems Mackey has been writing for over twenty years, “Song of the Andoumboulou” and “Mu” (though “mu no more itself / than Andoumboulou”). In the cosmology of the Dogon of West Africa, the Andoumboulou are progenitor spirits, and the song of the Andoumboulou is a song addressed to the spirits, a funeral song, a song of rebirth. “Mu,” too, splays with meaning: muni bird, Greek muthos, a Sun Ra tune, a continent once thought to have existed in the Pacific. With the vibrancy of a Miró painting, Mackey’s poems trace the lost tribe of “we” through waking and dreamtime, through a multitude of geographies, cultures, histories, and musical traditions, as poetry here serves as the intersection of everything, myth’s music, spirit lift.