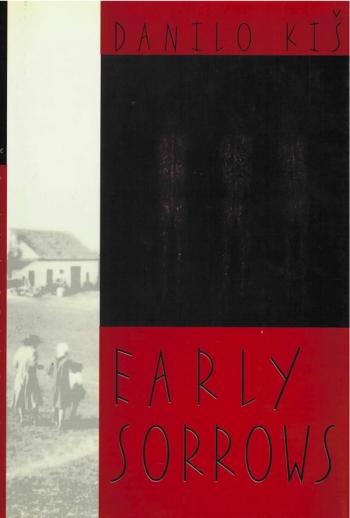

Originally published in Belgrade in 1969 and never before translated into English, Early Sorrows is a stunning group of linked stories that memorialize Danilo Kis’s childhood. Kis, a writer of incomparable originality and eloquence, famous for his books The Encyclopedia of the Dead, Hourglass, and A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, was born in 1935 in Subotica, Yugoslavia, near the Hungarian border. “Back and forth over this land, during Danilo Kis’s childhood, armies and ideologies washed with the brutal regularity of surf,” William Gass noted in The New York Review of Books. “As a small boy and a Jew, in such circumstances, he was naturally surrounded by death and lies.” All of the works of Danilo Kis show the crucial importance of his childhood experiences, but it is Early Sorrows that goes to the wellspring of his first bereavements. The twenty pieces that make up Early Sorrows strike various tones––from dreamy pastorals to exercises in horror. Kis’s ingenuity, lyricism, and tonal subtlety are caught in all their luster by Michael Henry Heim. Early Sorrows centers on Andreas Sam, a highly intelligent boy whose life at first seems secure. His mother and sister dote on him; he excels at school; when he is hired out as a cowherd to help with the family’s finances, he reads the day away in the company of his best friend, the dog. He can only sense that terrible things may be going on in the world. Soon soldiers are marching down the road, and then one day, many people from the village are herded together and taken away, among them, his father, the dreamer.