Hora de Clarice is a worldwide celebration which takes place each year on Clarice Lispector’s birthday in Brazil, Paris, Madrid, Lisbon, Frankfurt, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, and New York.

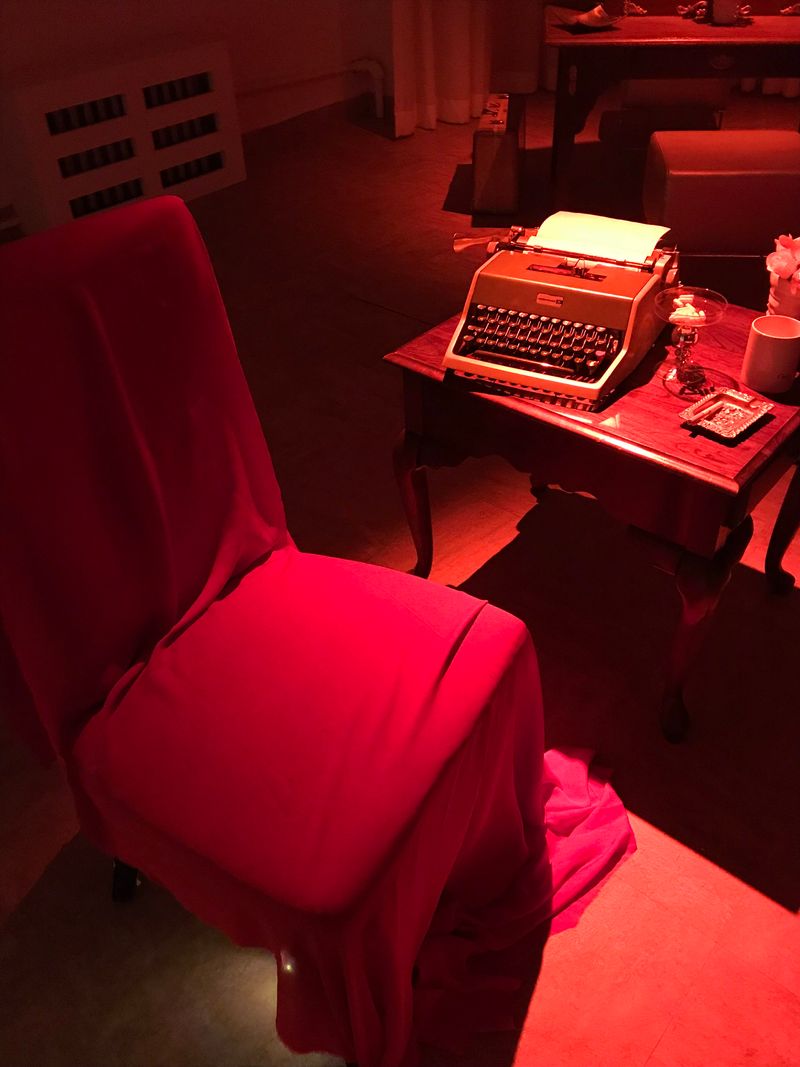

This year on December 10th, Group .BR partnered with Salles Institute, Brazil, for an evening of installations and performances from Inside the Wild Heart, an adaptation of Lispector’s first novel, in New York. Special guests Katrina Dodson and Rebecca Ariel Porte discussed Lispector’s stories “Mineirinho” and “The Egg and the Chicken” with moderator Mila Burns.

Thank you to all who came to celebrate Clarice Lispector. For those who couldn’t be there, for your reading pleasure, the amazing story of Mineirinho.

Mineirinho

Yes, I suppose it is in myself, as one of the representatives of us, that I should seek the reasons why the death of a thug is hurting. And why it does me more good to count the thirteen gunshots that killed Mineirinho rather than his crimes. I asked my cook what she thought about it. I saw in her face the slight convulsion of a conflict, the distress of not understanding what one feels, of having to betray contradictory feelings because one cannot reconcile them. Indisputable facts, but indisputable revolt as well, the violent compassion of revolt. Feeling divided by one’s own confusion about being unable to forget that Mineirinho was dangerous and had already killed too many; and still we wanted him to live. The cook grew slightly guarded, seeing me perhaps as an avenging justice. Somewhat angry at me, who was prying into her soul, she answered coldly: “It’s no use saying what I feel. Who doesn’t know Mineirinho was a criminal? But I’m sure he was saved and is already in heaven.” I answered, “more than lots of people who haven’t killed anyone.”

Why? For the first law, the one that protects the irreplaceable body and life, is thou shalt not kill. It is my greatest assurance: that way they won’t kill me, because I don’t want to die, and that way they won’t let me kill, because having killed would be darkness for me.

This is the law. But there is something that, if it makes me hear the first and the second gunshots with the relief of safety, at the third puts me on the alert, at the fourth unsettles me, the fifth and the sixth cover me in shame, the seventh and eighth I hear with my heart pounding in horror, at the ninth and tenth my mouth is quivering, at the eleventh I say God’s name in fright, at the twelfth I call my brother. The thirteenth shot murders me—because I am the other. Because I want to be the other.

That justice that watches over my sleep, I repudiate it, humiliated that I need it. Meanwhile I sleep and falsely save myself. We, the essential phonies. For my house to function, I demand as my primary duty that I be a phony, that I not exercise my revolt and my love, both set aside. If I am not a phony, my house trembles. I must have forgotten that beneath the house is the land, the ground upon which a new house might be erected. Meanwhile we sleep and falsely save ourselves. Until thirteen gunshots wake us up, and in horror I plead too late—twenty-eight years after Mineirinho was born—that in killing this cornered man, they do not kill him in us. Because I know that he is my error. And out of a whole lifetime, by God, sometimes the only thing that saves a person is error, and I know that we shall not be saved so long as our error is not precious to us. My error is my mirror, where I see what in silence I made of a man. My error is the way I saw life opening up in his flesh and I was aghast, and I saw the substance of life, placenta and blood, the living mud. In Mineirinho my way of living burst. How could I not love him, if he lived up till the thirteenth gunshot the very thing that I had been sleeping? His frightened violence. His innocent violence—not in its consequences, but innocent in itself as that of a son whose father neglected him. Everything that was violence in him is furtive in us, and we avoid each other’s gaze so as not to run the risk of understanding each other. So that the house won’t tremble. The violence bursting in Mineirinho that only another man’s hand, the hand of hope, resting on his stunned and wounded head, could appease and make his startled eyes lift and at last fill with tears. Only after a man is found inert on the ground, without his cap or shoes, do I see that I forgot to tell him: me too.

I don’t want this house. I want a justice that would have given a chance to something pure and full of helplessness in Mineirinho—that thing that moves mountains and is the same as what made him love a woman “like a madman,” and the same that led him through a door so narrow that it slashes into nakedness; it is a thing in us as intense and transparent as a dangerous gram of radium, that thing is a grain of life that if trampled is transformed into something threatening—into trampled love; that thing, which in Mineirinho became a knife, it is the same thing in me that makes me offer another man water, not because I have water, but because, I too, know what thirst is; and I too, who have not lost my way, have experienced perdition. Prior justice, that would not make me ashamed. It was past time for us, with or without irony, to be more divine; if we can guess what God’s benevolence might be it is because we guess at benevolence in ourselves, whatever sees the man before he succumbs to the sickness of crime. I go on, nevertheless, waiting for God to be the father, when I know that one man can be father to another. And I go on living in my weak house. That house, whose protective door I lock so tightly, that house won’t withstand the first gale that will send a locked door flying through the air. But it is standing, and Mineirinho lived rage on my behalf, while I was calm. He was gunned down in his disoriented strength, while a god fabricated at the last second hastily blesses my composed wrongdoing and my stupefied justice: what upholds the walls of my house is the certainty that I shall always vindicate myself, my friends won’t vindicate me, but my enemies who are my accomplices, they will greet me; what upholds me is knowing that I shall always fabricate a god in the image of whatever I need in order to sleep peacefully, and that others will furtively pretend that we are all in the right and that there is nothing to be done. All this, yes, for we are the essential phonies, bastions of some thing. And above all trying not to understand.

Because the one who understands disrupts. There is something in us that would disrupt everything—a thing that understands. That thing that stays silent before the man without his cap or shoes, and to get them he robbed and killed; and stays silent before Saint George of gold and diamonds. That very serious thing in me grows more serious still when faced with the man felled by machine guns. Is that thing the killer inside me? No, it is the despair inside us. Like madmen, we know him, that dead man in whom the gram of radium caught fire. But only like madmen, and not phonies, do we know him. It is as a madman that I enter a life that so often has no door, and as a madman that I comprehend things dangerous to comprehend, and only as a madman do I feel deep love, that is confirmed when I see that the radium will radiate regardless, if not through trust, hope and love, then miserably through the sick courage of destruction. If I weren’t mad, I’d be eight hundred policemen with eight hundred machine guns, and this would be my honorableness.

Until a slightly madder justice came along. One that would take into account that we all must speak for a man driven to despair because in him human speech has already failed, he is already so mute that only a brute incoherent cry serves as signal. A prior justice that would recall how our great struggle is that of fear, and that a man who kills many does so because he was very much afraid. Above all a justice that would examine itself, and see that all of us, living mud, are dark, and that is why not even one man’s wrongdoing can be surrendered to another man’s wrongdoing: so that this other man cannot commit, freely and with approbation, the crime of gunning someone down. A justice that does not forget that we are all dangerous, and that the moment that the deliverer of justice kills, he is no longer protecting us or trying to eliminate a criminal, he is committing his own personal crime, one long held inside him. At the moment he kills a criminal—in that instant an innocent is killed. No, it’s not that I want the sublime, nor for things to turn into words to make me sleep peacefully, a combination of forgiveness, of vague charity, we who seek shelter in the abstract.

What I want is much rougher and more difficult: I want the land.

Translated by Katrina Dodson