When I write poems, I sometimes pretend it’s not me but the language itself that’s writing. I pretend it’s possible to step back a bit from my human persona and to observe language from the outside, as if I myself had never used it.

I pretend language and the world have their own connection. Pretend the individual words, without me, are directly related to the phenomena they refer to. So that it becomes possible for the world to find its own meaning. A meaning that’s already there.

This is just something I pretend. But I also feel that it’s something I need to do. I need to find meaning in the world, not because I’ve dedicated myself to doing it, maybe not even because I want to do it, but because I, like any of the world’s other native inhabitants, can’t help creating meaning, the meaning that is already there and that unceasingly manages its own transformation, in the process that we call survival.

I can put it another way. My expressing myself here is no different in principle from a tree growing leaves. Self-protruding, self-regulating biological systems are basically the same, whether they’re called trees or humans.

As a human, naturally I have to admit that as I sit here by my window, I can see a tree, whereas the tree presumably can’t see me. But what does “see” mean? That’s human language. Of course it’s correct to say that the tree hasn’t seen anything, yet in its own way the tree has seen me, nevertheless. It has registered human presence, even if as nothing more than air pollution.

Then we could say this basically just shows that humans are more fully developed than trees and have power over things; that we’re the ones who can decide whether trees will die, and not vice versa. But who knows how the transformation might best be managed? Maybe what looks like forest die-offs is, more than anything else, a sign that we ourselves are in danger, that we ourselves could perish—after the forests do, of course.

But whether it happens before or after is, for that matter, less relevant to the trees’ welfare than to our own. After all, we haven’t demonstrated any ability to rise again from the earth after we die, whereas seeds that have lain hidden in the Egyptian pyramids have been shown to be viable today. So we can assume that trees will just hide in the earth and come up again in due time, sometime when air pollution and humans are gone. The trees will survive, though in that event, more than likely in the company of cockroaches than us.

Of course, that’s no way to see it. And yet. Maybe it shows that in actuality, the world can both read and be read. That impressions can be harvested just as grapes can. That we as humans can read a multitude of signs, from the motions of the stars and the clouds, through the migrations of birds and shoals of fish, to the language of ants and of swirling water at home in the kitchen sink. Everything from astronomy and invisible chemistry to biology and its climates. But ants too read. Trees too read and know within seconds when they should let their leaves droop, if their blossoming is endangered.

Still, we are, of course, unique. But only because the earth is unique. It’s the earth that has, in its biosphere, drafted the project called humanity, which is unique not so much because there are no other like us in our vicinity in space, and not so much because we can interpret sign systems and try to convert them to our language, nor because we can read the natural and historical progression of readability itself—no, essentially we’re unique only because we use the word god.

Because we have to imagine that we ourselves, after all our reading of ourselves and everything else, ultimately will reach the boundary of readability. And it may be this boundary, perceived in advance, that makes us unique. It’s at this boundary, which actually lies deep within our own thoughts, that we in passing carry on the conversations between readability and unreadability that we professionally called god.

And we have been carrying on that conversation for a long time. Since before we ever had a written language. Maybe almost before we had a spoken language. In any case before we compose the first poem, oral or written, because we already were aligned with the poem that is the universe’s own.

Along the way we’ve made various attempts to capture that poem, and we’ve called it everything from divine revelations to science. From the first holy scriptures that came into the world, such as the Bible, on through Novalis to Mallarmé, and in science on to the latest theories of the workings of the universe, a concept of the book of the world has existed, the book that expresses everything and thus halts the conversations between readability and unreadability within the word god. So to speak.

A concept that has always drawn sustenance from its own impossibility. It’s true that the bible is called divine revelation, but it is a revelation funneling into the provision that “now we can see through a glass, darkly, but then we shall see face to face”—“then” meaning at some future time when the world being revealed no longer exists.

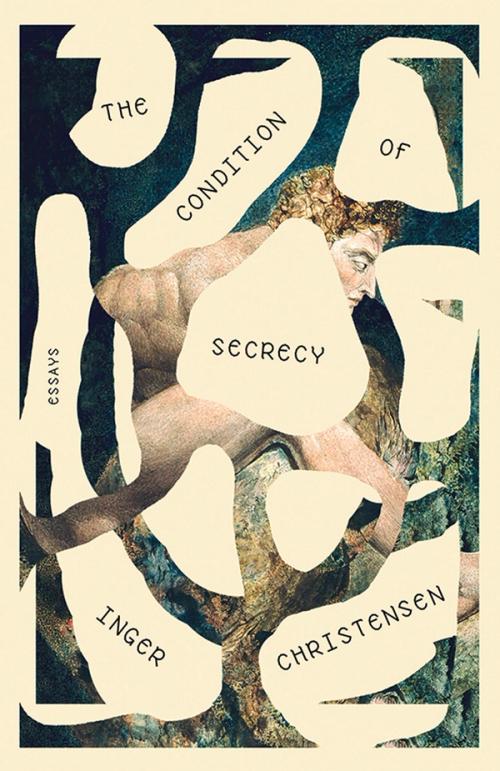

And when Novalis searches for the all-encompassing fusion of words and phenomena—“Das Aussere ist ein in einen Geheimniszustand erhobenes Innere” (“The outer world is an inner world raised to a condition of secrecy”)—and works his way toward the formula for that archetypal book, the task grows like wild weeds, because of course the more he gathers of it all, or reads his way into it all, the more it seems to spread, just as later, Mallarmé too begins to direct his attention more toward the emptiness between words than towards the words themselves.

And when science tries to write the book of the world, its attempts on the whole consist of constantly revised theories about the origins of the universe, its inner design and workings, theories that arise right at that same boundary, where the conversation between readability and unreadability can be carried on perfectly well, using terms such as chaos theory, fractals, and superstrings—but only because the word god sounds too overbearing.

In the human dimension the map must remain an abbreviation. And in the same way, language must remain an abbreviation for the world’s readability per se. A poetic abbreviation for all the sign systems in the universe, whose relationship and movements we can’t avoid reading. What Novalis calls “das seltsame Verhaltnisspiel der Dinge” (“the strange interplay of things”) and all the relationships in the world. This interplay of relationships is expressed in all sorts of self-protruding systems and the way they’re interwoven. In the human world, first and foremost, in language and mathematics as they’re interwoven within us. Among other things, in the form of poems.

If we provisionally pretend that the universe can read and write itself, we find ourselves in the middle of the poem called the Big Bang Theory. At the dawn of the universe, here’s what happened: everything, which at first was compressed into next to nothing (somewhere between 0 and 1), exploded and spread to all sides, and a motion that will continue until everything is spread so very thin that it will seem to disappear and become nothing again, or next to nothing. An image. Or a poem situated far out in unreadability, at the same time that we with our with our human language suggest that it could be able to read itself.

But whether poems are written in one way or another—whether I pretend it’s me or language itself doing the writing, whether I straightforwardly read the world or say that I, reading the world, as part of the world, and thus it is reading itself—regardless, I am and will remain the naive reader, a native inhabitant, an insider who can never see her world from the outside. And my poem will relate to the universe in the same way the eye relates to its own retina. But still, it sees. And it keeps reading.

(1991)