“Choose an author as you would choose a friend,” Wentworth Dillon, Earl of Roscommon, counseled aspiring translators some four centuries ago. But affinity, literary and otherwise, can be unpredictable. Under the fluorescent lights of the New York University basement classroom where I first read the poems of the Argentine poet Oliverio Girondo (1890-1967), I could never have imagined the challenging, whimsical companion he would become.

Girondo made a reputation for himself on both sides of the Atlantic with his debut collection, Veinte poemas para ser leídos en el tranvía [Twenty Poems to Read on a Streetcar], which in turn inspired the title of the recently published New Directions pamphlet. He further cemented his reputation by co-founding the avant-garde Martín Fierro group and penning the seminal manifesto of the Buenos Aires collective’s eponymous magazine.

Girondo released his next collection—Espantapájaros (al alcance de todos) [Scarecrow (Within Reach of All)]—with a wild publicity stunt. Following his own dictum that “a book should be made like a watch and sold like a sausage,” Girondo hired a funeral carriage and two drivers in formal attire to cart a giant papier-mâché “scarecrow” in a top hat and monocle around Buenos Aires while attractive young women sold copies of the book from a storefront downtown. The print run sold out almost immediately; the scarecrow was retired to the house on calle Suipacha where Girondo lived with his wife, the writer Norah Lange, to preside over the many animated literary fêtes they hosted.

The Scarecrow at his new home in the Museum of the City of Buenos Aires

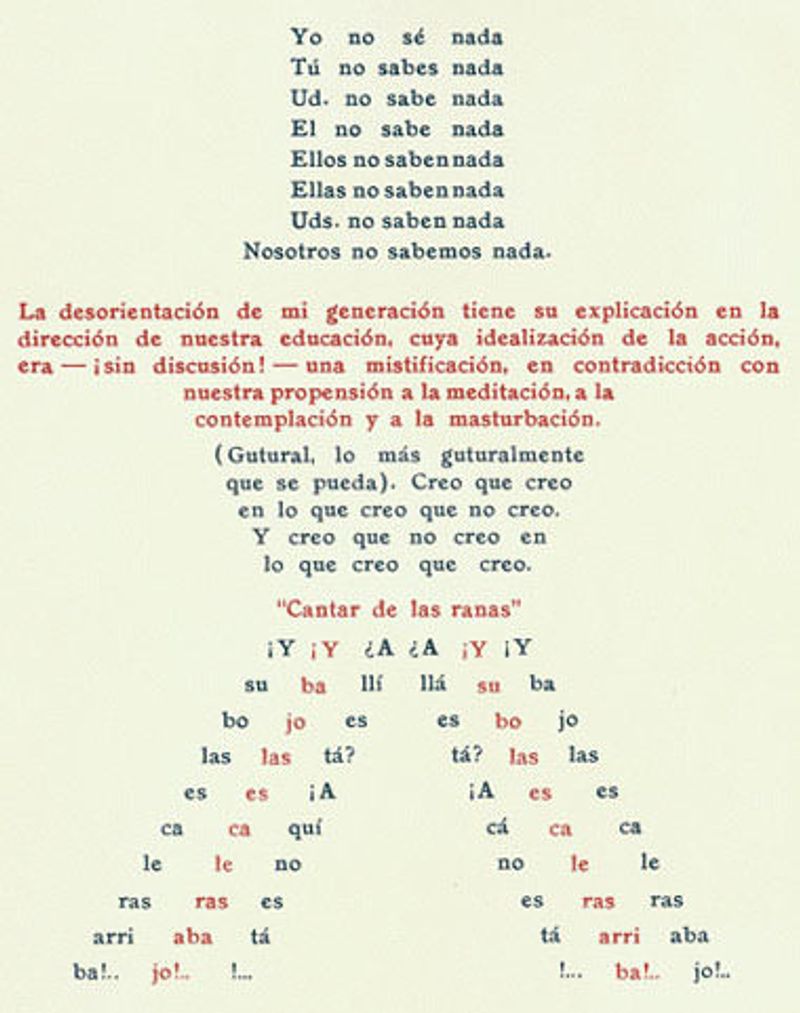

Scarecrow (Within Reach of All)—Girondo’s second venture into prose poetry—is introduced by a calligram in the shape of a scarecrow whose head is composed of a full declension of the phrase “to know nothing” and whose viscera assert, “I believe I believe what I believe I don’t believe.” It was this poem that I read in that basement classroom, and this poem that I happened upon again years later, while looking for material for a translation workshop. But it wasn’t until this second encounter that I was finally able to hear the magnanimous insolence of Girondo’s poetic voice—a defining characteristic of his early work.

Girondo’s scarecrow calligram

As it turns out, this proto-Concrete calligram was an ideal point of entry into Girondo’s work (fortunately, I did have a second chance to get a first impression). Condensing the gestures at undermining institutional authority—of universities, governments, businesses— seen throughout the poet’s oeuvre, the schoolhouse chant at the poem’s “head” calls its own pedagogical aim into question through its insistence on the absence of knowledge; the series of rhymes that follows performs a similar function, indicting the educational system and celebrating “our natural predilection for meditation, contemplation, and masturbation.” The gist: poetry is not something to be relegated to the ivory tower or the salon. It is something to be plucked like “scraps from the pavement” and appreciated in much the same way—on streetcars and in plazas, colloquially and viscerally.

This insistence on “guttural” expression is not only part of Girondo’s quest to democratize poetic form, it is also tied to his relationship to language. Much of the poet’s later work, in fact, tries to drive the written word—through phonetic play and neologism—in the direction of sensory experience, away from codified, “corroded” versions of itself. This is particularly true of his final collection, En la masmédula [In the Moremarrow; 1963], a kaleidoscopic tumult of denotation and sound, though there are signs of it in the poet’s previous work.

In the first book of Girondo’s poems that I translated—Persuasión de los días [The Persuasion of Days; 1942]—the natural realm is associated more than anything with this immediacy—the poetic voice moves from an urban sphere consumed by greed and indifference to a space where he can rediscover “the stream’s easy bareness” and other pleasures grounded more in hush than hustle. It features one of my favorite poems, “Join Your Hands,” a piece in which the interplay between artifice and appreciation, institution and instinct, is accentuated by the simplicity of its presentation.

JOIN YOUR HANDS

The people say: Dust Celestial Sepulchral, and are left calm, mollified, satisfied.

But listen to this cricket, that wisp of night, of a lunatic existence.

No is the time for it to sing. Now and not tomorrow. Right now. Here. At our side… as if there were nowhere else it could.

Do you understand? Me neither. I don’t understand a thing.

It’s not just your hands that are pure miracle. A misstep, a lost thought, and you might have been a fly, lettuce, a crocodile.

And then… that star. Don’t ask. Mystery!

The silence. Your hair.

And the passion, the acquiescence of the whole universe, it took to make your pores that nettle, that rock.

Join your hands. Amputate your braids.

_ In the meantime I’ll turn three somersaults._

* * *

Heather Cleary is a translator of Spanish literature as well as an editor at the Buenos Aires Review.

Published