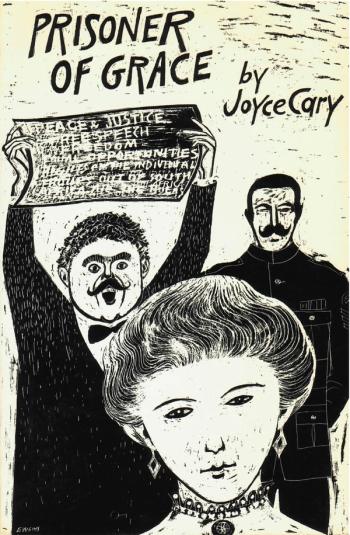

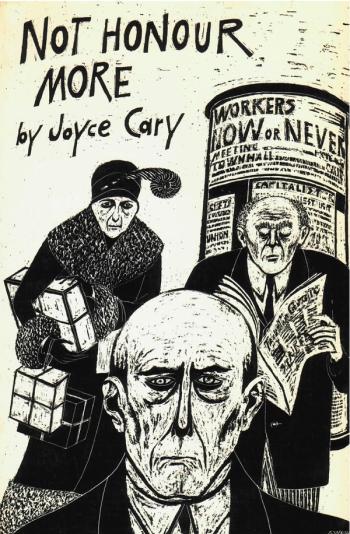

Joyce Cary (1888-1957) is indisputably one of the finest English novelists of this century. His reputation at his death equaled those of such contemporaries as Aldous Huxley and Evelyn Waugh. His exuberant style allowed him to create a vivid array of men and women whose stories embody the conflicts of their day and whose characters are beautifully realized. Written in his last years, his “Second Trilogy” (Prisoner of Grace, Except the Lord, and Not Honour More) shows the mature Cary at his most brilliant, as he unfolds the tragicomedy of private lives compromised by politics and religion. While in his earlier trilogy (Herself Surprised, To Be a Pilgrim, and The Horse’s Mouth) he pits the visionary artist against an indifferent but by no means dull world, in his masterful “Second Trilogy” he maps that gray landscape between good and evil where life is at its most dangerous. The concluding novel in Joyce Cary’s “Second Trilogy,” Not Honour More (1955) takes up at the point Prisoner of Grace (1952) ends. The setting is Palm Cottage, the remnant property of the Slapton-Latter family and now the scene of an unhappy ménage consisting of Captain Jim Latter (retired), his wife Nina (née Woodville), and her former husband, Chester Nimmo. It is 1926, the year of the General Strike. Nimmo, once a Cabinet Minister, sees the situation as his chance for a political comeback, while Jim, head of the emergency civilian police, feels it his duty to take his stand, however desperate, against “the grabbers and tapeworms… sucking the soul out of England.” For Nina, the trapped go-between, their inevitable clashes can lead nowhere but disaster. Not Honour More is Jim’s book, “my statement, so help me, as I hope to be hung.”