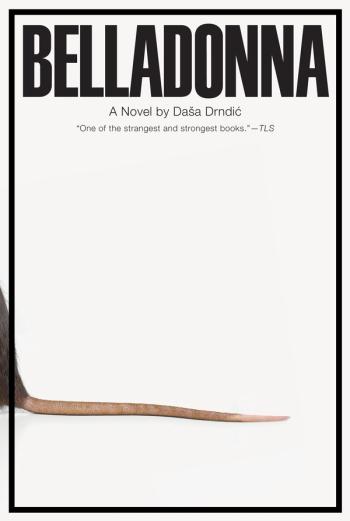

Belladonna: also known as deadly nightshade, devil’s berries, death cherries, beautiful death, devil’s herb, which sounds terrifying and threatening. Belladonna also carried a tamer name, dog’s cherry, and an almost magical one, fairy plant.

Andreas Ban, a psychologist who no longer psychologizes, a a writer who no longer writes, lives alone in a coastal town in Croatia. His body is failing him. He sifts through the remnants of his life—his research, books, medical records, photographs—remembering old lovers and friends, the tragedies of WWII, the breakup of Yugoslavia. Ban’s memories of Belgrade (which he thought he had left behind) and of Amsterdam (a different world and life) alternate with meditations on hole-ridden time (ebbing away through its perforations), on his measly pension, on growing old and fragile, on the intelligence of rats and the agelessness of lobsters, on deadly nightshade. He tries to push the past away, to “land on a little island of time in which tomorrow does not exist, in which yesterday is buried.”

Drndić leafs through the horrors of history with a cold unflinching wit. “The past is riddled with holes,” she writes. “Souvenirs can’t help here.” And they don’t.