The house I’m confined in is my father’s house in Auvergne, in France, in the Cantal, a mountainous region with small lakes that is often compared to Scotland for the beauty of its landscapes. The house is at the heart of a big village, in a small valley. The one beautiful thing about the village is its Romanesque church. Built in 1900, my house (it became mine after my father and sisters had died) is durable and cosy, but it’s not what you’d call a beautiful house. It has a small garden that gives me no end of trouble, since I know nothing about gardening and planting, or the lives of trees and hedges and flowers. I try to maintain a tired, hundred-year-old pear-tree that persists in putting forth flowers and then inedible fruit. On the day of my elder sister’s funeral, on October 23rd, 2018, one of the great birch trees in whose charming shade you could read in summer turned out to have been rotten and broke in two. I recently had an ash-tree cut back whose dense foliage was blocking the light in one of the bedrooms, and you would swear it was refusing to break into bud. My garden exists solely in what I have left untended: flowers I haven’t planted spring up everywhere. When I arrived here on March 16th, the day before the French lockdown began, the grass was strewn with pale-yellow-and-pink primroses; the following day, a shrub started to give out red and white flowers and seventeen daffodils appeared; the day after that, a mass of myosotis established itself beneath the Virginia creeper, then purple irises sprang up that were almost black. The less I tend my garden, it seems, the more it thrives.

The house my father was born in and would later retire to and occupy for nearly twenty years had previously belonged to my paternal grandparents, and before that to my paternal great-grandmother. Contained in it are three generations of objects, furniture, wallpaper, curtains, crockery. It’s a bit much. Each summer since my father’s death, I try to clear out and refurbish certain corners of the house, but I don’t get very far. I’ll be living with this charming but over-heavy burden, I suspect, to the very end.

My father’s house has always been the house of my confinement. It has always felt like a trap to me, and I’ve always done the canniest thing you can do when you live in a trap, which is to embrace it. When you embrace a trap, it becomes slightly less of a trap. My father who was theatrical, in the same way that my great-grandmother was very theatrical, used to say: if there’s a war one day, you’ll come and take refuge in the house! (By “you” he meant me and my sisters). I’ve always liked the prospect, of course, of having a place to take refuge in, should a war break out. When we learned of the existence of the virus and President Macron announced that we were at war, I didn’t hesitate for a second: I fled Paris and came and took refuge in my house. At the same time, I don’t like living here on my own, because the house is big and full of rooms and presences. And though I’m not afraid of those presences, it’s a bit strange to still feel all these empty rooms inhabited.

I try to follow (on television or the internet) the news of the pandemic and the situation in France and the rest of the world. I have constantly to fight off an unfortunate tendency I have always had of not quite realizing things. My friends send me emails and phone me, people’s minds are focused on the pandemic, I try to keep up. But, in truth, I’m more concerned about the black irises that have sprung up in my garden. Sometimes I think I’m like those women of old who would leave political discussions and worldly affairs to their menfolk while they went about embroidering a coverlet or a piece of tapestry work. This indifference, which borders at times on stupidity, has bothered me for years (and some friends don’t hesitate, quite rightly, to try and shake me out of it), but I can remember finding very early on a sort of authorization for it in a book by Lou Andreas-Salomé, though I can no longer recall if it was The House or The Erotic (and I have no way of checking, since the books are back home on my shelves in Paris), in which she compares the movement and restlessness of spermatozoa with the inertia of egg cells to explain the masculine need to go out into the world and the feminine need to stay at home. I was so struck by this (admittedly rather bizarre) interpretation that I can still see myself, at the age of twenty, stopping in my tracks on the Place de l’Odéon in Paris to think about it. Since then, each time someone upbraids me for not taking enough interest in worldly affairs, or on the many occasions when I’m incapable of conducting a conversation on a particular subject, I’m instantly reminded of the elderly face of Lou Andreas-Salomé, whom I once had a photo of, looking distinctly dreamy, on my wall at home.

In my mountain village, like everywhere in France, we’re not allowed to walk outside for more than an hour each day and have to remain within one kilometer of our homes. Gendarmes keep watch in the village and roundabouts. Not being able to meet people, not being permitted to embrace or touch anyone, is tiresome but manageable. Not to go walking in country lanes is much more difficult. One of my methods for embracing the trap of my own home has always been to walk endlessly in the surrounding countryside. So even now, every day I pick up a walking-stick or an umbrella – and at that point, of course, I immediately think of Robert Walser, especially when I have an umbrella, for there are several well-known photos, probably taken by Carl Seelig, that show him walking along a footpath or a country lane with a rolled umbrella in his hand – I go out through the garden, which is behind the house and faces the countryside, and the moment the village is behind me, disappear down little footpaths that can’t be seen from the road, nor by gendarmes. What strikes me just now is how silent the countryside is, apart from the birdsong, which is shrill. But coronavirus or no coronavirus, the trees, the hedgerows, the flowers, the leaves, the grass, the streams and the pebbles are going about their annual spring undisturbed. It’s the same impression I’ve always had when walking in the countryside: after my death, these footpaths, these thickets, these woods, these meadows, these clumps of flowers, these streams will be exactly the same, as if I had never passed that way.

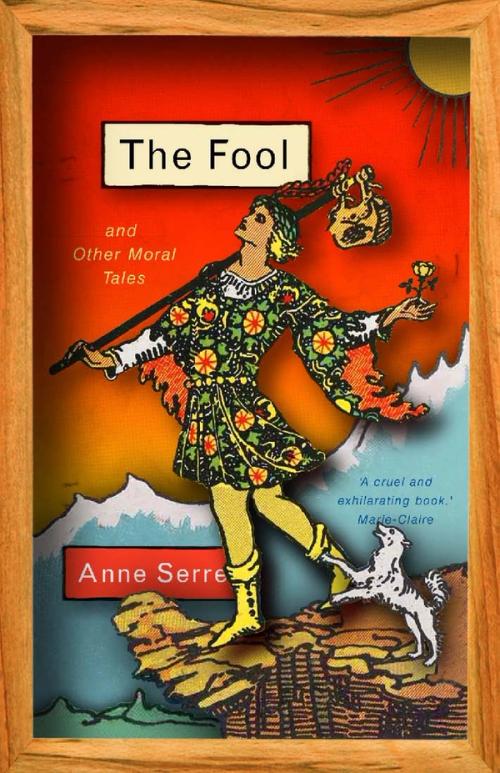

Anne Serre

Published