“What would American poets and critics do without the Central Europeans and the Russians to browbeat themselves with?” Maureen McLane exclaimed in the Chicago Tribune some years back: “Miłosz, Wisława Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski, Zbigniew Herbert, Joseph Brodsky — here we have world-historical seriousness! Weight! Importance! Even their playfulness is weighty, metaphysical, unlike barbaric American noodlings!” For some time now, Anglo-American authors have tended to see Eastern Europe, with its twentieth century sufferings, as a perverse promised land for modern writing, with Poland in particular serving as a kind of shorthand for “The Oppressed Country Where Poetry Still Matters.” I will not attempt to speak for all the poets McLane has assembled here. Szymborska for one, though, would be shocked to find herself ranked among the metaphysically serious and universally significant world powers of modern poetry. She celebrates the “joy of writing” in one famous lyric.

She is even more persuasive on the highly underrated joy of not writing she extols in “In Praise of My Sister”:

When my sister asks me over for lunch, I know she doesn’t want to read me her poems. Her soups are delicious without ulterior motives. Her coffee doesn’t spill on manuscripts.

Szymborska is preoccupied here, as throughout her work, with the relationship between poetry and the daily life that surrounds it, feeds it, and sometimes altogether ignores it. She has nothing but sympathy for the labors of would-be writers generally: “My first poems and stories were bad too,” she confesses in an interview with her friend Teresa Walas. The texts that make up her typically idiosyncratic “How to (and How Not to)” guide are culled from the advice she gave — anonymously — for many years in Literary Mailbox, a regular column in the Polish journal Literary Life.

She deals less gently, though, with those who scorn the sheer drudgery it takes to do anything well, be it soup-making or sonnets. “You write, ‘I know my poems have many faults, but so what, I’m not going to stop and fix them,’” she chides one novice, a certain Heliodor from Przemyśl: “And why is that, oh Heliodor? Perhaps because you hold poetry so sacred? Or maybe you consider it insignificant? Both ways of treating poetry are mistaken, and what’s worse, they free the novice poet from the necessity of working on his verses. It’s pleasant and rewarding to tell our acquaintances that the bardic spirit seized us on Friday at 2:45 p.m. and began whispering mysterious secrets in our ear with such ardor that we scarcely had time to take them down. But at home, behind closed doors, they assiduously corrected, crossed out and revised those otherworldly utterances. Spirits are fine and dandy, but even poetry has its prosaic side.” (Szymborska used the first-person plural not as the queenly prerogative of a future Nobel Laureate, but to maintain her anonymity, since Polish grammar relentlessly reveals its user’s gender, and she was the only woman on Literary Life’s editorial staff who answered letters.)

She goes no easier on would-be novelists. “You have compiled an extensive list of writers whose talent went unrecognized by editors and publishers who later shamefacedly repented,” she tells a certain Harry, from Szczecin: “We instantly caught your drift and read the enclosed feuilletons with all the humility our errors warrant. They’re old hat, but that’s not the point. They will certainly be included in your Collected Works so long as you also produce something along the lines of David Copperfield or Great Expectations.”

Poor Welur from Chełm gets even shorter shrift: “‘Does the enclosed prose betray talent?’ It does.”

Translators, for what it’s worth, fare no better. “The translator must not only stay faithful to the text,” she scolds H. O. from Poznań: “He or she should also reveal the poem’s full beauty while retaining its form and suggesting the epoch’s style and spirit. In your version, Goethe becomes a writer whose odds of achieving world glory are slim.”

“True, Éluard did not know Polish” she tells Luda from Wroclaw: “But did you have to make it so obvious in your translations?”

“Poets are poetry, writers are prose,” Szymborska comments in her resolutely anti poetic “Stage Fright” — or so public opinion would have it.

Prose can hold anything including poetry, but in poetry there’s only room for poetry— In keeping with the poster that announces it with a fin de siécle flourish of its giant P framed in a winged lyre’s strings I shouldn’t simply walk in, I should fly . . .

Szymborska stubbornly insists on art’s “prosaic side.” “Let’s take the wings off and try writing on foot, shall we?” she urges the hapless Grażyna from Starachowice in one letter. “I sigh to be a poet,” exclaims Miss A. P from Białogard. “We groan to be editors,” Szymborska responds, “at such moments.”

She returns time and again to the mundane business of writing properly, that is to say, painstakingly and sparingly. “You need a new pen,” she advises Mr. G. Kr. of Warsaw: “The one you’ve got keeps making mistakes. It must be foreign.”

Her own favorite writing utensil, an old friend of hers once told me, was the wastepaper basket: she threw away at least ninety percent of what she wrote. My own experience bears this out. Some years back, Szymborska relayed the poems from her volume Enough to an international team of translators by way of her secretary, Michał Rusinek (she never mastered the Internet). We received strict instructions shortly afterward to destroy one lyric and replace it with a revised text: the final version could not coexist with what had just become the penultimate draft. I did as she asked and deleted the draft without reading it. I suspect her other translators did too. We knew the rules.

Clearly she would like more writers to follow her lead. At the very least they should equip themselves properly for the long trek ahead. “You ask in rhyme if life makes cents [sic],” she remarks to Pegasus from Niepolomice: “My dictionary answers in the negative.”

“You treat free verse as a free-for-all,” she scolds another would-be poet, Mr. K. K. from Bytom: “But poetry (whatever we may say) is, was, and will always be a game. And as every child knows, all games have rules. So why do the grown-ups forget?”

The poet’s work, Szymborska remarks in her Nobel Lecture, “is hopelessly unphotogenic. Someone sits at a table or lies on a sofa while staring motionless at a wall or ceiling. Once in a while this person writes down seven lines, only to cross out one of them fifteen minutes later.” But the poet’s daily life is not drudgery alone. Or rather, the daily grind — the poet’s or anyone’s, for that matter — is anything but in the eyes and mind of an attentive writer. “Even boredom should be described with passion,” she reminds Puszka from Radom: “You should start keeping a diary . . . You’ll soon see how many things happen even on days when nothing seems to be happening.” (Her own lyric “May 16, 1973” is a case in point.)

Nonstop gloom and despair quickly wear out their welcome. “Your existential woes come a little too easily,” she reprimands Bolesław L-K. of Warsaw: “‘Deep thoughts,’ dear Thomas says (Mann, of course, who else), ‘should make us smile.’ Reading your own poem ‘Ocean,’ we found ourselves floundering through a shallow pond. You should think of your life as a remarkable adventure that’s happening to you. That is our only advice at present.”

And one final remark, worth remembering perhaps when daffodils and jonquils begin to bloom once more: “We automatically disqualify all poems about spring as a matter of principle. This topic no longer exists in poetry. It continues to thrive in life of course. But that is a different matter.” “Don’t bear me ill will, speech, that I borrow weighty words / then labor heavily so that they may seem light,” Szymborska writes in“Under One Small Star.” She kept her own literary labors strictly offstage.

She didn’t lecture on her craft. She didn’t lead master classes in creative writing or devote essays to the art of verse. “I’ve always had the sneaking suspicion I’m not very good at it,” she confesses in her — notably brief — Nobel Lecture. Not so. She was very good — but only in disguise.

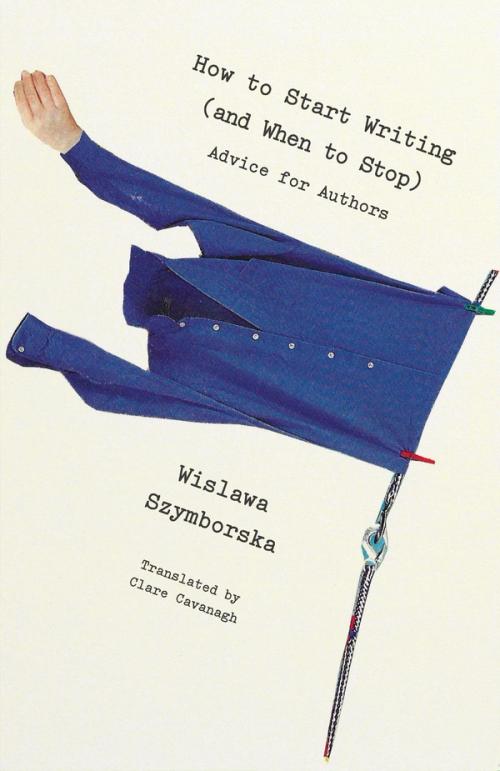

Revelation through concealment shapes her own work, of course. Wit, sympathy, and others’ voices combine to extraordinary effect in poem after poem: think of her Cassandra, her Byzantine mosaic, the occasional visitor from outer space. The strategic “we” she employs in How to Start Writing (and when to stop) does more than guide its readers through the joys — and miseries — of writing (and not writing) well. Her seriously lighthearted alter ego provides the closest look we’re likely to get at the marvelous workshop in which she drafted, revised, discarded, and sometimes, mercifully, even preserved the poems that make up her small, but weighty oeuvre.

“Such is life,” as she warns one would-be writer: “Brief, but each detail takes time.”

—Clare Cavanagh

Published