As author

The Wisdom Of The Heart

Sextet

The Colossus Of Maroussi

Sunday After The War

The Book Of Friends

A Devil in Paradise

Aller Retour New York

Into the Heart of Life

Letters To Emil

From Your Capricorn Friend

Just Wild About Harry

The Smile At The Foot Of The Ladder

The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

The Cosmological Eye

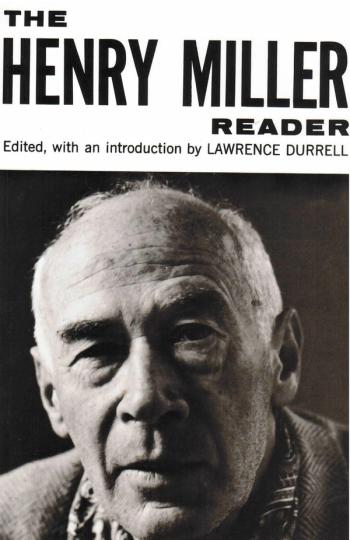

The Henry Miller Reader

Stand Still Like The Hummingbird

Henry Miller On Writing

The Time of the Assassins

The Books In My Life

Remember To Remember

Big Sur and the Oranges Of Hieronymus Bosch

As contributor

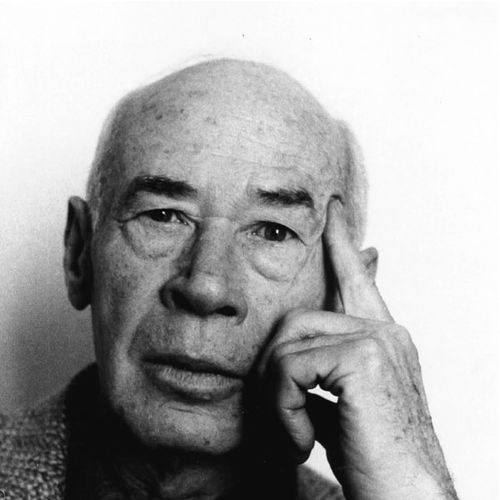

Henry Miller

Henry Miller (1891–1980) was born in New York, and spent his childhood in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn. In the late ’20s, Miller came to Paris with his wife June, and became acquainted with Anaïs Nin, who would become his lover and patron. Nin was the first publisher of Tropic of Cancer, which was the subject of a landmark obscenity trial when it was published in the U.S. in 1961. Miller’s writing, which was often sexually explicit, blended fiction, memoir, personal philosophy and social commentary. Forbidden by authorities, his books were smuggled into the U.S. and became highly influential on the new generation of Beat writers. His later years were spent writing and painting in Big Sur, on the coast of California.